Vancouver’s home prices remain dizzyingly high, but after a spectacular run lasting several years, they started to cool off in 2018.

The turn has would-be buyers and sellers heading into 2019 wondering how long this period will last and whether prices will hold or tumble.

Trying to call the timing and degree of a market correction is usually a mug’s game.

After all, when prices were rising by double-digit percentages with no seeming end, experts were baffled, quarter after quarter.

Still, there is a great deal of pressure to make some sense of it all.

This is a province where real estate-related transactions, including construction, account for as much as a quarter of the economy, by some estimates. It’s a city and surrounding area that was at the top of lists tracking the developed world’s most overheated housing markets.

Homes are for living in, but it’s undeniable there is a part of Vancouver real estate that has also become an asset class for investors.

And so, it’s not just buyers and sellers yearning for a crystal ball to see where prices will go, but also economists and analysts, who are digging into information about debt loads and household incomes to make predictions. Others are weaving into their calculations figures such as anticipated population growth and supply of new housing.

And then, there are some observers who have taken to charting patterns in historical data to say what might happen.

Stress test hit sales for first-time buyers

To recap, for many Vancouver home-price watchers, 2018 started off with mortgage stress testing rules coming into effect in January. These were introduced by the federal banking regulator to keep homebuyers across the country from taking on levels of debt that might be too risky. The intent was to guard against highly leveraged borrowers, especially in hot markets such as Vancouver and Toronto, defaulting on mortgage payments if interest rates rise.

And so, many first-time buyers found themselves qualifying to borrow about 20% less than what was available to them before. This had quite an immediate effect on Metro Vancouver presale condo sales in February and March, according to Michael Ferreira, managing partner at Urban Analytics, which tracks pricing and other data about the feasibility of condo projects for developers.

“It impacted certain parts of the market first, especially (sales for) entry-level and end-user units (as opposed to units bought by investors),” Ferreira said.

The way this shut out first-time buyers was frustrating for them, but it also highlighted how expensive even some of the cheaper, lower-end units are in relation to local incomes.

Some buyers with an existing mortgage who wanted to move and buy a more expensive property were also caught off guard when they couldn’t just take the amount they had already had approved by banks in the past and automatically put it to a new purchase. They too needed to re-qualify by meeting the standards of the stress test, which snagged some deals.

At the end of February, the provincial government released its budget, which included a rise in the foreign-buyers tax from 15 to 20% and announced a 0.5% speculation tax on homes left vacant in certain regions, including Metro Vancouver.

“There was the addition of taxes and policies targeted at the demand side of the market,” said Ferreira. “It wasn’t anything really tangible, but they impacted buyer psyche and sentiment about the government doing more to slow the market, to bring prices down.”

Meanwhile, there was a sea change going on in what had been some of the highest flying single-family home markets: Vancouver’s west side and West Vancouver.

Prices there had been driven by an infusion of money from mainland China, part of what has been described by Bloomberg BusinessWeek as being “one of the largest financial flows of the 21st century,” capital flight estimated by the Institute of International Finance to be in the hundreds of billions of U.S. dollars, starting in mid-2014. Along with this, major banks and their private banking businesses offered easy credit to high net worth, low risk borrowers, and there was a host of local real estate players eager to make their share as home prices surged.

These factors were related to each other “not in a linear way, but they had geometric relationships that came together,” said urban planner Andy Yan, director of Simon Fraser University’s City Program.

He asked: “So, how does it unwind or run out of gas? What happens when one or more of these factors disappears or changes? The price increases weren’t incremental going up. They were somewhere between incremental and exponential.”

One of the biggest shifts that has happened is a retreat of money from China. In the summer of 2016, the provincial government introduced a foreign-buyers tax of 15% on residential property (but not presale condos) in Metro Vancouver. At the same time, the mainland Chinese government began making it increasingly harder to move large amounts of money out of the country.

Although the number of detached homes selling on the west side and in West Vancouver had been tapering for some time before and certainly after these moves, prices did not follow in tandem right away.

While the Greater Vancouver Real Estate Board’s home price index for all residential properties showed modest gains compared to the year before, in June 2018, it stopped rising. In July, the index slipped 0.6% from the previous month. For detached homes on the west side, the board’s home price index showed a year-on-year drop of 8.4% and a drop of 8.3% for detached homes in West Vancouver.

Signs of a correction

This was a change, but others looking at average or median prices and drilling into specific housing types and neighbourhoods were seeing some price declines that had been going on for longer and were more dramatic.

By summer, some realtors and observers were signalling that a correction was underway. They pointed to July figures from SnapStats Publishing Company, showing that median prices for detached homes on Vancouver’s west side were down 26 per cent in a year, dropping by just under $1 million from $3.8 million to $2.8 million. In West Vancouver, detached home prices were logging a 30 per cent fall or a $1.1-million decline, from $3.6 million in December 2017 to $2.5 million in July.

It was argued that prices of detached homes in these areas were generally a harbinger of what was to come in other less expensive areas and housing types.

After all, when the market was on the rise, sharp price gains were seen first here in late 2014 before spreading to other areas and then later into condo and townhomes.

So, the same reasoning, in reverse, was that if prices were starting to drop for detached houses on the west side and in West Vancouver, there would be a chain reaction where sellers would have less wealth to use as buyers elsewhere and also have less wealth to pass on to their children or others to use as entry-level buyers.

“All of a sudden, would-be buyers (were) not sure if their existing single-family home would sell or sell at high enough a price to cover the condo they wanted to buy. In a sense, they felt if the price of their home has fallen, then the price of that project should fall too. There was a drop in urgency to buy,” said Ferreira, describing how this impacted higher-end, luxury projects targeted at downsizers in areas such as the Cambie Corridor, downtown Vancouver and South Surrey.

In reaction to this, and as projects that had once been oversubscribed took longer to sell and more units went sitting, developers started to offer various incentives to spark sales, including the lowering of prices.

More selective buying

There’s still underlying demand, but it’s much more selective, looking much harder at price, location and the brand, reputation and track record of a developer, said Ferreira.

In late September, the municipal elections brought in a fresh set of councils with more than a few elected on platforms to promote greater housing affordability. Shortly after, municipalities such as North Vancouver and White Rock set an immediate new tone for the pace of development with the cancelling or curtailing of certain condo projects.

The challenge with reduced activity for developers and their lenders, said Ferreira, was that construction costs and land values hadn’t fallen. Faced with greater risk and less profit, there has been an uptick in developers walking away. Instead of holding land to possibly develop later as they may have done in the past, some are cutting their losses.

Putting the impact of major, sweeping trends aside, what this means for the extent of price adjustments at specific projects will be a calculus of all of the above details.

The shifts are already happening at projects that are selling successfully. In Burnaby, presale condo prices for projects in the Brentwood mall area in the spring of 2018 were around $1,100 a square foot. Now, they are about $1,000, said Ferreira. Also in Burnaby, at Metrotown, prices had been around $1,200 a square foot and now they are around $1,170 a square foot, according to Ferreira.

“In places such as Richmond and Coquitlam, there is quite a bit of new supply coming in, so that will keep prices in check. Whereas, it’s fair to say in North Vancouver and White Rock (where councils have strongly signalled there won’t be as much imminent supply), it’ll be different.”

Big picture

Back to the big picture, in a nutshell, “something happened (in the Vancouver housing market) in 2015 that none of our brilliant models were able to capture,” wrote Toronto-based economist Benjamin Tal in a December report published by CIBC Capital Markets.

“We believe that 2015, and part of 2016, saw a significant increase in speculative activity, leading to an unsustainable surge in Vancouver home prices.”

“In many ways, what we’ve seen (since) is an undoing of gains made during an abnormal period,” said Tal.

It’s hard to parse out the impact of individual factors in a perfect storm, but there’s agreement, prices in Vancouver will more acutely feel the impact of measures introduced by federal and provincial governments to quell debt levels and demand.

Tal wrote that sales in Vancouver were harder hit by the mortgage stress test rules and taxes, “while the damage in Toronto was more limited ….. That’s not a big surprise since the regulations probably affected Vancouver to a greater degree given the more stretched affordability.”

Looking ahead, he sees that population growth in Vancouver has been lagging behind Toronto’s over the past two years, while the supply of highrise condo units has increased strongly. It means “the number of completed and unabsorbed units in Vancouver is on the rise, while that measure is still trending down in Toronto.”

Stephen Brown, a London-based senior Canada economist at Capital Economics, made a similar point.

“Strong population growth means the 100-plus cranes currently dotting Toronto’s skyline are not quite as excessive as they seem …(However), newly completed, unoccupied units have been marching higher in Vancouver.”

By Brown’s count, there are currently 42,000 units under construction in Vancouver compared to 71,000 in Toronto. Vancouver is “building 1.2 units for every person that arrived in Vancouver in the past year, compared to just 0.5 in Toronto.”

“The upshot of all this is that there are numerous reasons to think that Vancouver house prices are more vulnerable to a correction than those in Toronto … There is greater reason to think that the regulation-induced downturn in sales will be sustained and will lead to a drop in house prices.”

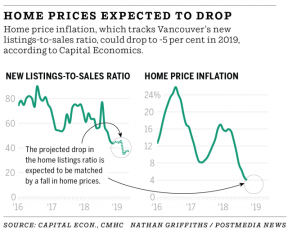

“Currently, the Vancouver new listing-to-sales ratio suggests annual house price inflation could drop to -5% next year, from 4.6% in October. Given the coming increase in supply will likely prompt a further rise in listings, we wouldn’t be surprised if the picture deteriorated further in coming quarters,” said Brown.

There are other economists, including Central 1’s Vancouver-based Bryan Yu, who are also predicting “subdued home sales and flat home values through 2021,” because of the “drag” of the stress test, more taxes to curb demand and higher interest rates.

The year ahead will see the speculation tax on homes left vacant in Metro Vancouver increase to 2% for foreign owners and “satellite” families where income is earned offshore. It will also see the province implement an “additional school tax for higher valued” homes, meaning 0.2% on those worth between $3 million and $4 million and 0.4% on those worth above $4 million.

Historical death stars and run-ups

One lone observer comes to a similar forecast looking at less fundamental, but more technical data.

Dane Eitel, a Vancouver realtor and analyst, took Vancouver house price data going back decades and plotted “death crosses,” which are basically when the line representing short-term average price crosses below the line for long-term average price.

It’s an indicator that immediate demand and price momentum are fizzling and there is the coming of longer-lasting decline. The method is used by some to gauge stock market trends, but it’s sometimes dismissed for putting aside all other factors except the relationship between short-term versus long-term average price.

Eitel says there have only been eight “death crosses” in Vancouver housing since 1978, which is as far back as the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver keeps numbers for average pricing. The last one was in 2012, but it only lasted a year. Eitel thinks the current death cross, which he plotted in November, is more like the one seen in the 1990s due to a more similar run-up in pricing.

Eitel predicts Vancouver detached homes that are currently averaging $1.7 million will bottom out at the $1.4 million mark in 2020-2021 before starting a new run-up in prices that ends with the average detached home price hitting $2.8 million in 2028.

Vancouver Home Prices in 2018 & Where They Might Go in 2019 by Joanne Lee-Young | Vancouver Sun

Recent Comments